Metal Toad Hosts Women Who Hack

On Sunday, we welcomed Women Who Hack, a monthly gathering "for women who want to hack on projects with or around other women.

I've been going around town giving a talk on the history of women in computers.

Jul 12, 2017

I've been going around town giving a talk on the history of women in computers. During my research, I came across so very many women I’d never heard of before, but who had made indelible marks on the history of computing. I decided to write a blog series about these amazing software pioneers who just happen to be women. But I didn’t just want the blogs to be boring old history lessons. Instead, I wanted to give examples and do research on the actual code these pioneers made.

Memo, dated January 1951, National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics:

"Effective this date, Dorothy J. Vaughan, who has been acting head of the West Area Computers unit, is hereby appointed head of that unit."

And just like that, after doing the job for two years, Dorothy Vaughan became the first African American of any gender to become a supervisor at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which would later be replaced by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958.

So, have you watched Hidden Figures? That movie was not only amazing, it was also ridiculously, stupendously, amazingly overdue.

I guess I should feel glad that these stories of the amazing women who contributed and pioneered the world of software are coming out now. But I wish we didn't view these stories with such incredulity. I hope the stories of amazing women of any and all colors who are pioneers in their field are as numerous as any other hero or role model, one among many of the same gender and color (and ethnicity, etc). I want us to be drowning in strong technical female role models!!

But let's talk about Dorothy Vaughan. She was one of the three women portrayed in Hidden Figures, and the one who I identified with the most. Why, you ask? Well, because she decided to teach herself Fortran. Yep, she was the computer nerd of the bunch! In the early 1960s NACA decided to bring in some (non-human) computers — namely an IBM 7090, with 24,000 calculations per second! - to eventually replace the human computors, who were mostly female. (An iPhone 6 can process 3.36 billion instructions per second. That's a tad bit faster, I guess.) These behemoths, which apparently were too big to go through the doorway, were brought in to help the newly-established Analysis and Computation Division, a group which would find themselves on the frontier of computing. Dorothy created a future for herself and her group in this emerging technology by teaching not only herself Fortran, but the rest of her West Area computors as well, becoming a leading expert Fortran programmer in the division. She also contributed to the Scout Launch Vehicle Program, one of the nation's most successful satellite launch vehicles.

But she was much more than a brilliant mathematician and a pioneer for black women in science and technology. She worked as a teacher, teaching math and French, before starting her NACA career. She was also an accomplished pianist, playing at her church, which furthers my claim that math and music go hand in hand. Not only that, but she was a dedicated mother to her six children and is survived by numerous grandchildren, with many doctors, scientists and ministers among them.

Can you guess what the code section of this is gonna be? Yep. Intro to Fortran!

The first thing you need to do is decide which version of Fortran you'd like to use. There's, like, 500 different variants (that might be an overstatement, but not by much), after all. You see, since Fortran was one of the very first programming languages, they didn't think about the whole 'establishing standards' thing, and therefore developers went wild (since it was so popular), tweaking it for their own uses. They finally started reeling things in around 1966. So yeah — a bit of standardization can be a good thing!

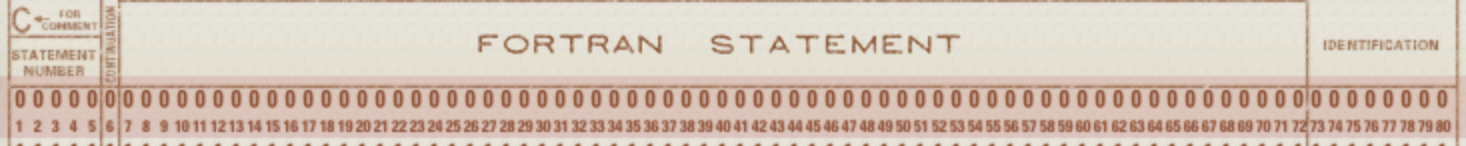

There are two basic types of Fortran: fixed form layout and freeform layout. Fixed form variants are older, having sprung from the model of punch cards, and followed a very strict (or fixed!) layout: each line is 72 characters exactly. (Well, 80, but I'll get to that.) Blanks outside quoted literals are ignored. So you could have a variable named AC DC, and Fortran wouldn't blink an eye. You could even write the 'then' part of an if-then statement like this: TH E N. As for how to properly use aaaaaall those 80 characters, consider the following:

Characters 1-5 is where those statement labels go, and should be numeric and unique. The exception is a C, to indicate that the line is nothin' but comment.

The character at column 6 is where your continuation character should go, saying 'Hey I'm just continuing from the last line!' This can be anything except a 0.

Characters 7-72 is where you need to squeeze in all your code.

Those last 8 characters from 73 to 80 are not processed. You can put stuff there, but the compiler will totally ignore it. At least until you get into later versions of Fortran, that is.

For the purposes of our really grokking what writing code was like in Dorothy's day, we're gonna stick with fixed form layout. The specific version I'll use is FORTRAN IV, which was the result of the first attempt at standardization done in 1966. So without further ado, let's look at some sample code!

First, we'll need to have a way to compile our Fortran code. I used the open source gfortran compiler for MacOS, but they've got binaries for Windows and Linux available for download, as well as instructions on how to use it. Install that, and we're off and running!

1. Hello World

1 C ----------------------------- 2 C LOOK AT ME I'M A COMMENT WHEE! 3 ! AND I CAN GO ON AND ON AND ON AND ON 4 C ----------------------------- 5 WRITE (6,100) 6 100 FORMAT(17H Why hello there!) 7 STOP 8 END

Breaking it down:

In lines 1, 2 and 4 the C denotes a comment line. Everything after that line is ignored by the compiler. Line 3 has a bang or exclamation mark in column 6, which indicates that it's a continuation from line 2; therefore a continued comment.

Line 5 is where we start to get into the meat of the matter: WRITE(6, 100) means we should write to the the standard output which Fortran knows as unit number 6, and we should use the format instructions on the line with a statement number of 100, which is found on line 6. In Fortran 77, we could swap the 6 for an asterisk, which would default to standard output. Standard input was 5, or again an asterisk.

On line 6 we have a FORMAT statement: FORMAT(24H Why hello there!). This statement is not called in the regular flow of execution, but must be referenced, as it is in line 5. If the compiler hit a format statement during normal execution flow, it would be a no-op. The 24H in the FORMAT statement is called a 'Hollerith constant'; since Fortran IV had no character data types, characters were placed into a numeric variable using a Hollerith constant (named for Herman Hollerith). The 24H indicated it was a Hollerith constant with 24 characters in it, and the space immediately following indicates a newline. (Yes, I could have just used 17H and it would have worked fine too, since there are 17 characters after the H. I just was being roomy). As you can see, there's no string delimiters. In Fortran 77, the CHARACTER data type was introduced, making the use of Hollerith constants obsolete.

Lines 7 and 8 have the STOP and END statements. The STOP statement is semi-optional; it denotes the logical end of the program and ends execution, but the program will probably still function. The END statement is required as the final statement, or it will not compile.

So that covers basic output... What about input?

2. Keyboard Input

So I'm cheating a bit here...this example starts to use some of the features of Fortran 77, like the previously mentioned CHARACTER data type:

01 C -----------------------------

02 C Simple FORTRAN IV I/O Example

03 C -----------------------------

04 CHARACTER*60 NAME1

05 WRITE(6,400)

06 400 FORMAT('Enter your name:')

07 READ(5,200) NAME1

08 200 FORMAT(A60)

09 WRITE(6,300) NAME1

10 300 FORMAT('Hello, ',A60)

11 STOP

12 END

Lines 1, 2, and 3 are more comments.

On line 4 we're initializing a CHARACTER variable called NAME1 with a character length of 60: CHARACTER*60 NAME1

On line 5 we have another WRITE function, again writing to standard output (6) and calling the format function found at statement label 400. As you can see, the statement labels don't need to be in any sort of order whatsoever.

LIne 6 is our 400 FORMAT function: FORMAT('Enter your name:'). As you can see, we now have string delimiters!

Next on line 7 comes a new statement, the yin to WRITE's yang: READ. It is exactly like the WRITE statement in that it requires an input number (or asterisk, for default standard input), and a format function. The input number for the keyboard is 5, and our format command has a statement label of 200, which gives us our read statement of READ(5, 200) NAME1. Note that we're storing the input in our NAME1 variable that we initialized earlier, by adding a variable list. We could have multiple variables in our list, and the READ function would stick the input into the variables according to the format instructions. In this case, of course, we only have one variable.

Line 8 is the format statement for the READ. The A60 means it is alphanumeric data (A) that is 60 characters long.

Line 9 is our last WRITE. This one has another variable list following the function call, with one variable in it — our NAME1 variable from the beginning again. The format function that is referenced will then output the string — 'Hello, ', and then append any variables in the variable list according to the formatting instructions. Again, you could have multiple variables — and multiple format instructions — all comma separated.

So! I think that wraps up my start to Fortran (mostly) VI! What I found extremely fascinating is how simple, loose, and fluid this language was at this stage in its development. You can really see the underpinnings of many of the programming constructs we take for granted now being slowly edified as newer standards tried to address the wildly differing approaches and customizations that kept cropping up, keeping those things that worked and discouraging the ones that didn't.

I'll leave you with an image of a FORTRAN punch card that may be just like the ones Dorothy used. with one of the lines of code from the prior example.

On Sunday, we welcomed Women Who Hack, a monthly gathering "for women who want to hack on projects with or around other women.

Devops has been picking up steam since around the year 2009. ( It could be argued it was around in other forms longer but for argument's sake let's...

Metal Toad Mentorship Saturdays are a place for people of all skill levels and development disciplines to get help and advice on their careers and...

Be the first to know about new B2B SaaS Marketing insights to build or refine your marketing function with the tools and knowledge of today’s industry.