I've been going around town giving a talk on the history of women in computers. During my research, I came across so very many names of women who had made indelible marks on the history of computing that I'd never heard before. I decided that for my inaugural blog post at Metal Toad (Yes, I know I've been here for like over a year now. What? I've been busy!) I would love to do a blog series about these amazing software pioneers who just happen to be women. But instead of this just being a boring old history lesson, I will attempt to give examples and research the actual code contributions that these women have made.

So, let's start! And of course, we must begin with that illustrious figure, Ada Lovelace.

1. The History

Ada Lovelace was the only (legitimate) offspring of that crazy Romantic poet, Lord Byron. And while he is often considered brilliant, fashionable and certainly prolific, he was also pretty much a free-wheeling, carousing ladies man. Or man's man. Either, really, if the rumors are true. But all those good times not only cost money, but created so many of those 'it's complicated' kind of relationships (note: having a relationship with your half-sister is generally frowned upon, buddy), and he hoped his marriage to the down-to-earth Annabella Milbanke, niece to his friend Lady Melbourne, would allow him to pay his debts and at least give the appearance of breaking ties to those difficult relationships. The marriage lasted only a year, with Annabella leaving him and taking their only daughter Ada with her.

Ada's mother was well educated in literature, philosophy, and had a knack for mathematics. In what may have been an attempt to quash any of her father's moody temperament, Annabella insisted on Ada's studies of math and science - not common for a lady of the 1800s to study. One of her tutors, Mary Somerville, was one of the first women to be admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society.

Ada quickly showed a penchant for numbers and language, which eventually led to her meeting inventor and mathematician Charles Babbage at the age of 17. They struck up a friendship and Babbage became her mentor, encouraging her continued studies in advanced mathematics. He even dubbed her at one point the 'Enchantress of Numbers.' Now, Babbage was a very well respected mathematician of the day, but as an inventor his ideas never quite seemed to find purchase. His true passion was the idea of calculating machinery, and with that idea he invented a design for a Difference Engine, which could tabulate logs and trig functions by evaluating differences to create polynomials. Sort of like the original graphing calculator, except without the graphing part. But no sooner than he finished this design, he thought up a new machine which could tabulate *any* mathematical function - not just polynomials. More like...a computer!

Ada was fascinated with Babbage's inventions and the possibilities it presented. She was asked to translate an article on the analytical engine by an Italian engineer - Luigi Menabrea (also future Prime Minister of Italy). She not only translated the original French text into English, but also added her own thoughts and ideas at the prompting of her mentor. The article, along with her notes, was published in 1843 in an English science journal. Ada used only the initials "A.A.L.", for Augusta Ada Lovelace, in the publication.

In her notes, she described how codes could be created for the machine to represent letters and symbols along with numbers. She theorized, among other things, a method for the engine to repeat a series of instructions - sound familiar? Yes, she just came up with the idea of loops. It is for this inspired insight that she is considered to be the first computer programmer.

I like to think that her father's creative influences fueled her creative ways of looking at logic and mathematics, and allowed her to see possibilities that others did not.

Now...onto the tech!

2. The Tech

First, for reference, here is a link to Ada's notes on the translation.

Having no other way at hand to analyze her contributions, I proceeded to review the notes that were found at the link above. Preceding it is the actual article written by Menabrea.

One of the first things that struck me in her notes, titled 'Notes by the Translator', is how she stressed the importance of separating the mathematical operation from the thing being operated upon.

In studying the action of the Analytical Engine, we find that the peculiar and independent nature of the considerations which in all mathematical analysis belong to operations, as distinguished from the objects operated upon and from the results of the operations performed upon those objects, is very strikingly defined and separated."

Scientific Memoirs, Vol. 3, page 692

And how those operations could be applied to any object:

"It may be desirable to explain, that by the word operation, we mean any process which alters the mutual relation of two or more things, be this relation of what kind it may. This is the most general definition, and would include all subjects in the universe."

Scientific Memoirs, Vol. 3, page 693

She goes on to speculate how these operations could ultimately be applied to music:

"The operating mechanism can even be thrown into action independently of any object to operate upon (although of course no result could then be developed). Again, it might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine. Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent."

Scientific Memoirs, Vol. 3, page 694

And then, looping structures!

It is obvious that this mechanical improvement is especially applicable wherever cycles occur in the mathematical operations, and that, in preparing data for calculations by the engine, it is desirable to arrange the order and combination of the processes with a view to obtain them as much as possible symmetrically and in cycles, in order that the mechanical advantages of the backing system may be applied to the utmost. It is here interesting to observe the manner in which the value of an analytical resource is met and enhanced by an ingenious mechanical contrivance.

Scientific Memoirs, Vol. 3, page 720

Wow. Ok. As a side note, one of her tutors was Augustus De Morgan (of De Morgan's laws fame) so her connections to the fledgling world of logic and computing are pretty solid.

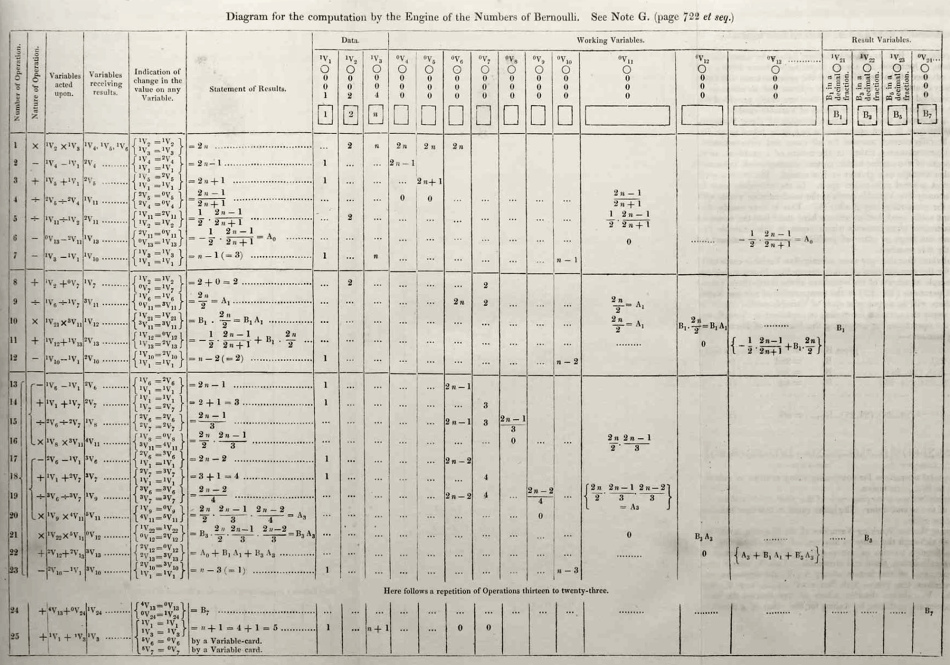

As she is famous for publishing what is widely considered to be the world's first computer algorithm, let's take a look at it:

It appears to be more of a sequence of operations that the machine should perform, than a true algorithm. It appears that the only columns that are of true significance to a computer would be the first 4 columns or so:

- Column 1: Order of operations, or line number

- Column 2: Type of operation (+, -, / or *)

- Column 3: The two variables upon which to perform the operation

- Column 4: Where to store the result.

It would not be too difficult to emulate the instructions that would have been fed into the engine via punch cards. I'm working on faithfully recreating these operations in a Python script - check out the script on GitHub, and let me know what you think!

--

Did you like this blog post? Check out History of Computer Girls, Part 2: Margaret!